Is this stealth nasal infection linked to leaky gut?

MARCoNS stands for multiple-antibiotic resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococci, and a MARCoNS infection has been linked to a range of chronic health concerns, including leaky gut syndrome and allergies.1

We’ve already offered a broad overview of what MARCoNS is and why it matters, so this time we’ll dig a little deeper to examine intestinal permeability — and the links between MARCoNS and “leaky gut syndrome.”

Two decades ago, the concept of a leaky gut and leaky gut syndrome was often sneered at or dismissed as an imaginary complaint by conventional medicine. “That’s ridiculous — our gut doesn’t leak.”

There’s no shortage today, though, of current research demonstrating the importance of the intestinal barrier for health.2

The problem is that the intestinal barrier — with the clinical significance of damage to the gut lining — remains somewhat unclear to conventional medicine. (Not so in functional medicine.)

A lot can go wrong when your gut starts to ‘leak’

The comment that “you are what you eat” has been around for so long that it’s become quite glib, but the more accurate, updated version of that statement that “you are what you absorb” is still just catching on.

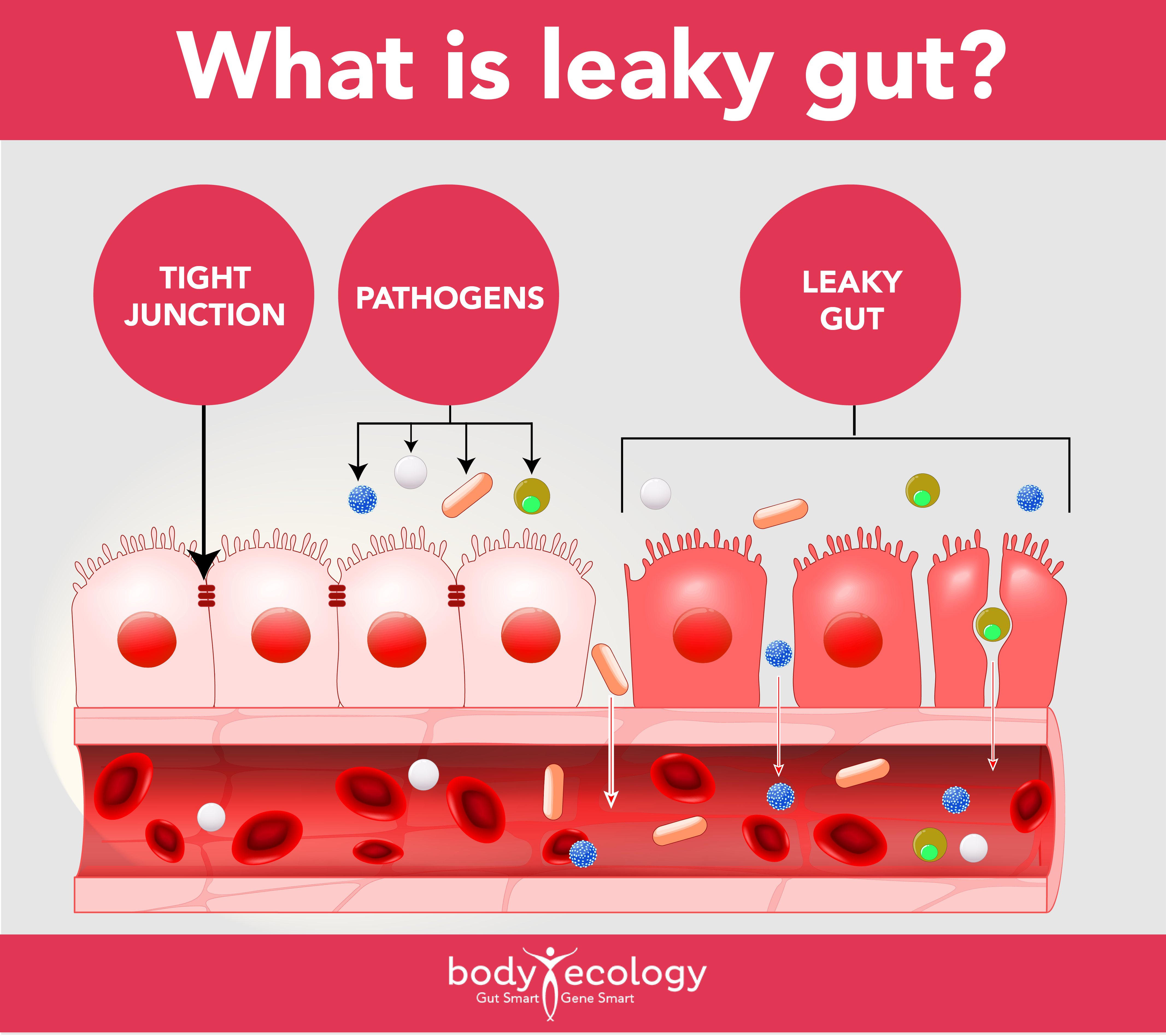

This absorption isn’t only about nutrients; it’s also about the fact that an intact, well-functioning intestinal barrier stands guard, allowing in what your body wants and needs, while protecting you against the dangers of the outside world — like invasion of microorganisms and undigested molecules — that can trigger an unwanted autoimmune response.

The intestinal barrier is always permeable.

It has to be to perform its job, but tight junctions form a close-fitting, continuous barrier, uniting the cells lining the intestinal tract, and regulate the movement of molecules and substances across the intestinal barrier and into the bloodstream. Damage to this barrier will cause inflammation there and then abnormal and increased intestinal permeability.

The tight junctions won’t be tight anymore. You can’t see your gut lining, but imagine that you rubbed sandpaper on your arm. Your skin, which is naturally permeable, will now be damaged, inflamed, and “leaky.” This is what a “leaky gut” looks like: inflamed. A leaky gut really means — an intestinal barrier that is inflamed.

Leaky gut syndrome may contribute to undesirable inflammatory reactions in the liver, brain, and elsewhere in the body and may even trigger metabolic diseases, such as insulin resistance.3

This is why a damaged and inflamed gut lining is now linked to the development of metabolic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, cardiometabolic diseases, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).4-6 A constant in all autoimmune conditions is an inflamed gut lining.

Inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), speed up the rate at which the epithelial cells are shed. Where there’s a high level of inflammation or chronic inflammation, this increased shedding can create gaps too big for tight junction proteins to fill.7

These gaps offer opportunities for molecules and pathogens to get in or out of the intestines in a way that can harm health.8

Get in good with your gut. Download our free guide on how to master at-home colon cleansing.

What helps leaky gut? Investigating MARCoNS and underlying triggers

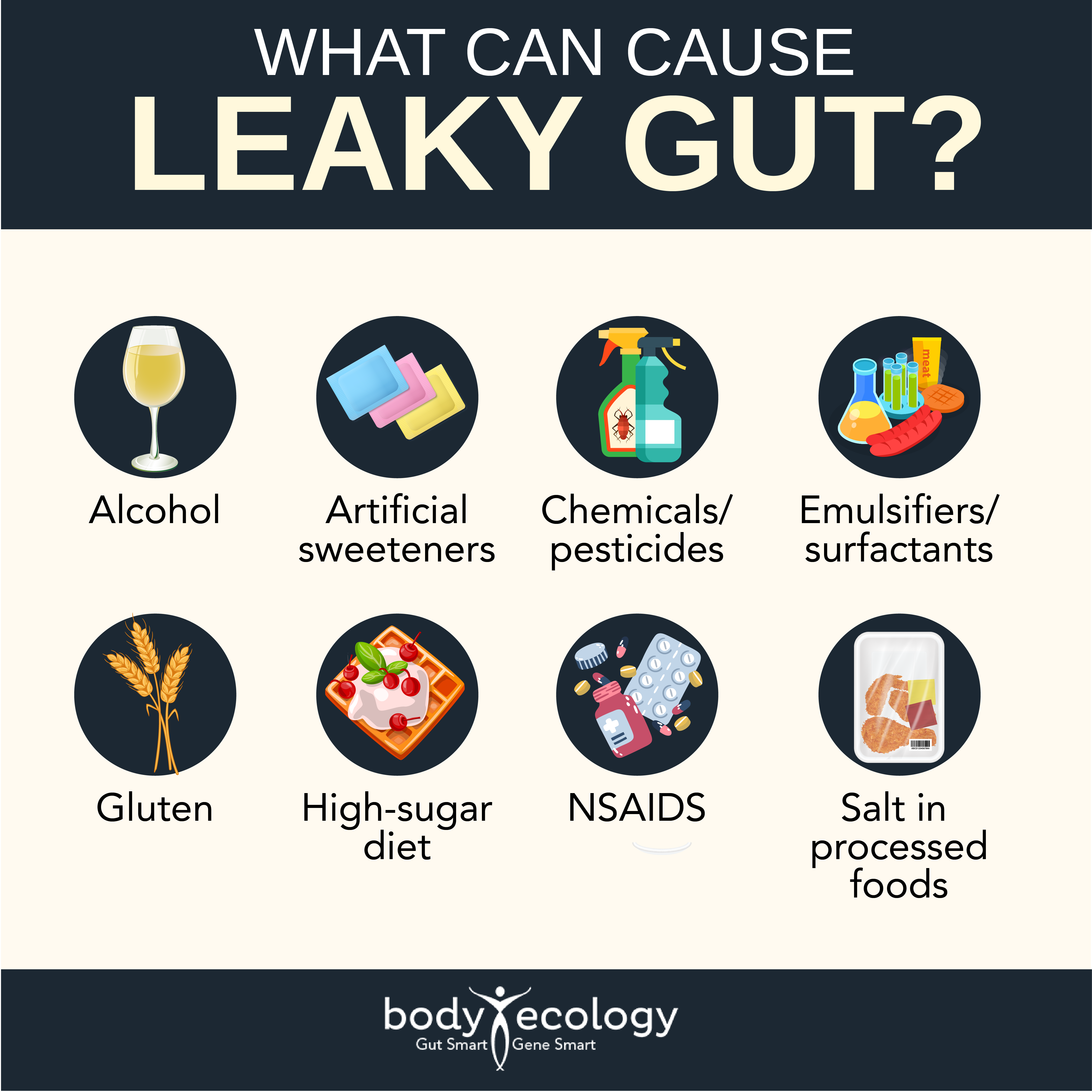

So, what contributes to leaky gut syndrome? Unfortunately, many things, including:

- Gluten – This protein is blamed more than anything else.

- Diets high in sugar – Adopting a high-fat diet is also known to cause alterations in gut microbiota and increase gut permeability.9

- Commercial salt used in all processed foods

- Alcohol – Alcohol and “empty nutrition” food and beverages can increase intestinal permeability.10,11

- Artificial sweeteners

- Chemicals and pesticides

- Emulsifiers and surfactants – Used to help ingredients combine (like oil and eggs) in mayonnaise.

- NSAIDS – Like Aleve and ibuprofen.

Your genes also influence the effectiveness of your gut barrier, as do environmental factors and illnesses associated with inflammation.

These may include:

- Celiac disease

- Food allergy

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Metabolic diseases, like diabetes

Perhaps the most common cause of an inflamed gut lining is infections caused by pathogens.

For example, you may be familiar with Clostridium difficile.12 This anaerobic bacterium is a key driver of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and is a commonly acquired infection in long-term care facilities and hospitals for this reason (and from unwashed and contaminated food).13

C. difficile causes diarrhea by producing two toxins that inflame the epithelial cells lining the gut. More water ends up in the gut, leading to diarrhea.

Many other pathogens interact specifically with the tight junctions of your gut. Antibiotics and other drugs can also disturb the intestinal mucus layer, reducing gut barrier protection, and yet these are often given to eliminate the infection.14

MARCoNS can alter the structure and function of tight junctions to increase permeability of the intestinal barrier too.15 The antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus bacteria have even been shown to affect the tight junctions in the skin barrier.16 And, MARCoNS impacts the intestinal barrier by secreting toxins that decrease the production of Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone (MSH).1

MSH is a hormone made in the pituitary gland:

- It regulates many other hormones and plays a role in inflammatory responses and immune defenses against microbes.

- MSH also defends against MARCoNS, including killing MRSA, which means a MARCoNS infection — causing low MSH — represents a vicious cycle.17,18

Low MSH may increase susceptibility to fungal infection from mold exposure, as well as symptoms like chronic fatigue, chronic pain, insomnia, and sexual dysfunction.1 MSH plays a key role in the processing of the protein gliadin in the intestines, with low MSH leading to increased inflammation and intestinal gaps remaining open when they should be closed.19

So, what helps leaky gut begin to heal? One major contributor to intestinal barrier function is — you guessed it — your microbiome.

Increasingly recognized as part of the functional immunological barrier, your gut microbiome is involved in metabolic processes, affects the mucosal immune system, and may have a significant impact on intestinal permeability, which is where allergies come in.20 We’ll look at how probiotics could prove potent in helping to repair a leaky gut in the next article in our series.

REFERENCES:

- 1. Jennifer Smith, NMD. “Chronic Inflammatory Response Syndrome: Diagnosis and Treatment – A Paradigm Change for 21st Century Medicine.” Lifestream Wellness Clinic, 2019.

- 2. Bischoff SC, Barbara G, Buurman W, et al. Intestinal permeability–a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:189. Published 2014 Nov 18. doi:10.1186/s12876-014-0189-7.

- 3. Houser, M.C., Tansey, M.G. The gut-brain axis: is intestinal inflammation a silent driver of Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis?. npj Parkinson’s Disease 3, 3 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-016-0002-0.

- 4. Serino M, Chabo C, Burcelin R. Intestinal MicrobiOMICS to define health and disease in human and mice. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012 Apr;13(5):746-58. doi: 10.2174/138920112799857567. PMID: 22122483.

- 5. Delzenne NM, Neyrinck AM, Cani PD. Modulation of the gut microbiota by nutrients with prebiotic properties: consequences for host health in the context of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Microb Cell Fact. 2011;10 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S10. doi:10.1186/1475-2859-10-S1-S10.

- 6. Spruss A, Bergheim I. Dietary fructose and intestinal barrier: potential risk factor in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Nutr Biochem. 2009 Sep;20(9):657-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.05.006. PMID: 19679262.

- 7. Kiesslich R, Goetz M, Angus EM, Hu Q, Guan Y, Potten C, Allen T, Neurath MF, Shroyer NF, Montrose MH, Watson AJ. Identification of epithelial gaps in human small and large intestine by confocal endomicroscopy. Gastroenterology. 2007 Dec;133(6):1769-78. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.011. Epub 2007 Sep 16. PMID: 18054549.

- 8. Kiesslich R, Duckworth CA, Moussata D, et al. Local barrier dysfunction identified by confocal laser endomicroscopy predicts relapse in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2012;61(8):1146-1153. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300695.

- 9. Serino M, Luche E, Gres S, et al. Metabolic adaptation to a high-fat diet is associated with a change in the gut microbiota. Gut. 2012;61(4):543-553. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301012.

- 10. Massey VL, Arteel GE. Acute alcohol-induced liver injury. Front Physiol. 2012;3:193. Published 2012 Jun 12. doi:10.3389/fphys.2012.00193.

- 11. Pendyala S, Walker JM, Holt PR. A high-fat diet is associated with endotoxemia that originates from the gut. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(5):1100-1101.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.034.

- 12. Marcus Steinemann, Andreas Schlosser, Thomas Jank, Klaus Aktories. The chaperonin TRiC/CCT is essential for the action of bacterial glycosylating protein toxins likeClostridium difficiletoxins A and B. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2018; 201807658 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1807658115.

- 13. Nasiri MJ, Goudarzi M, Hajikhani B, Ghazi M, Goudarzi H, Pouriran R. Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile infection in hospitalized patients with antibiotic-associated diarrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaerobe. 2018 Apr;50:32-37. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2018.01.011. Epub 2018 Jan 31. PMID: 29408016.

- 14. Ng KM, Ferreyra JA, Higginbottom SK, et al. Microbiota-liberated host sugars facilitate post-antibiotic expansion of enteric pathogens. Nature. 2013;502(7469):96-99. doi:10.1038/nature12503.

- 15. Berkes J, Viswanathan VK, Savkovic SD, Hecht G. Intestinal epithelial responses to enteric pathogens: effects on the tight junction barrier, ion transport, and inflammation. Gut. 2003;52(3):439-451. doi:10.1136/gut.52.3.439.

- 16. Ohnemus U, Kohrmeyer K, Houdek P, Rohde H, Wladykowski E, Vidal S, Horstkotte MA, Aepfelbacher M, Kirschner N, Behne MJ, Moll I, Brandner JM. Regulation of epidermal tight-junctions (TJ) during infection with exfoliative toxin-negative Staphylococcus strains. J Invest Dermatol. 2008 Apr;128(4):906-16. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701070. Epub 2007 Oct 4. PMID: 17914452.

- 17. Sana Mumtaz. Lipidated Short Analogue of α-Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone Exerts Bactericidal Activity against the Stationary Phase of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Inhibits Biofilm Formation. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 44, 28425–28440. Publication Date:October 26, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.0c01462.

- 18. Shireen, Tahsina & Singh, Madhuri & Dhawan, Benu & Mukhopadhyay, Kasturi. (2012). Characterization of cell membrane parameters of clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus with varied susceptibility to alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone. Peptides. 37. 334-9. 10.1016/j.peptides.2012.05.025.

- 19. Váradi J, Harazin A, Fenyvesi F, et al. Alpha-Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone Protects against Cytokine-Induced Barrier Damage in Caco-2 Intestinal Epithelial Monolayers. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0170537. Published 2017 Jan 19. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170537.

- 20. Samadi N, Klems M, Untersmayr E. The role of gastrointestinal permeability in food allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018 Aug;121(2):168-173. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.05.010. Epub 2018 May 25. PMID: 29803708.