What are oxalates in food doing to your body? It’s not pretty.

When your gut bacteria are out of whack, this can contribute to oxalate sensitivity. Body Ecology’s Culture Starter provides healthy, beneficial bacteria that greatly enhance digestion and contribute to a lavish inner ecosystem.

The first thought that normally comes to mind when you eat a spinach salad or drink a green smoothie is that you’re going to eat something truly healthy that will provide your body with some powerful nutrients to thrive off of.

For some, that can be the case. Yet for many others who have a hard time processing the high oxalate levels in spinach, it can be a problem.

Some practitioners, researchers, and nutritionists have been focusing more on studies and anecdotal examples of how oxalates produced by the body and in food can be a major factor as to why those with gut issues have unresolved symptoms.

For some people, they may be able to eat high-oxalate foods without an issue. Yet for some who seemingly make healthy choices — like adding high-oxalate almond milk to smoothies — they could be affecting their health by creating an abundance of oxalates in their system.

Nutritious ingredients that could be messing with your microbiome

Oxalates, along with their acidic form of oxalic acid, are organic acids that derive from three primary sources:

1. Food and drink.

2. Metabolic functioning.

3. The elevated presence of funguses, such as penicillium, aspergillus, and candida albicans yeast.1

Those who have low levels of vitamin B6 are particularly susceptible to inflammation caused by the yeast candida albicans, which is often found surrounding calcium oxalate stones in the kidney.2,3 The presence of these biological factors, coupled with a diet high in oxalates (between 120 to 1,000+ mg/day), often produces elevated levels of oxalates in urine and plasma samples of kidney stone patients.4

Studies showing the dangers of oxalates in food have been around for decades. Couple that with the fact that humans, starting from when we began to crawl, used to have more oxalobacter formigenes — a beneficial gut bacteria that has been reduced over time possibly due to antibiotic use.

This gut bacteria is shown in studies to be helpful in lowering urinary oxalate output.5 Evidence also indicates a probable link between gut bacteria and sensitivities not only to oxalates but histamine, lectins, and salicylates in food. Glyphosate, antibiotics, chronic infections (like yeast), and their relationship to gut bacteria may be behind why many people are reacting more now to these compounds in food.

Additionally, elevated oxalate levels have also been linked to many other disorders, including autism, kidney disease, fibromyalgia, and vulvodynia in women.6

4 potential causes of high oxalate levels

Contributors may include:

1. Permeable gut

- When your gut bacteria are out of whack, including not having enough o. formigenes and having intestinal permeability, this can contribute to oxalate sensitivity.

- It’s said that oxalates are primarily absorbed in the stomach, not necessarily the intestines.

2. Candida

- Powerful enough to destroy your ability to process and get rid of oxalates, candida yeast produces a precursor to oxalates. It’s actually able to transform collagen into oxalate crystals.

- One of the many reasons why bone broth is seen as a benefit to the production of collagen is because it can help tremendously with healing a gut. Yet, when a high amount of collagen merges with candida, especially if someone is vitamin B6 deficient, the results can be toxic.

- Specific anti-fungal herbs have also been shown to effectively kill candida, like oregano leaf, curcumin (from turmeric), garlic, and the inner bark of the pau d’arco tree. Specific fermented foods can also help to rebuild a healthy inner ecosystem.

3. Dietary deficiencies

- Oxalates present in either the diet or from candida albicans can also bind heavy metals and other vitamins and minerals in the digestive tract.

- This may lead to varying dietary deficiencies.7

4. Oxalate metabolism

- Oxalates are produced by the body and are also ingested when we eat certain foods. The amount varies daily and depends on the person.

- Oxalic acid from food is converted to glycolate and then glyoxylate. From here, it can bind to a mineral and form oxalate, or it can form glycine. Then, the enzyme alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase (AGXT) can take over at this point.

- Yet, if you’re genetically deficient in AGXT, you have lower levels of AGXT needed to override glyoxylate forming oxalate.

How your body develops high amounts of oxalates can be directly related to your genetic predisposition. In the genetic diseases hyperoxaluria type I and II, there is a deficiency in enzyme activity, leading to suspected higher than normal oxalate levels.8

Weston A. Price notes that “it has been found that one-third of the people with oxalate toxicity have this genetic variant, and 53 percent of them are likely to have acute, very severe neurotoxicity versus only 4 percent in those with normal genotype expression.”

New to Body Ecology and don’t know where to begin? BE Essentials has it all.

6 warning signs of high levels of oxalates

As oxalates and oxalic acid can crystallize within the body in various forms, there are varying degrees of symptoms related to high oxalate levels. Some can be harder to pinpoint than others.

In addition to muscle and joint pain, here are some signs to look for that could indicate oxalates may be to blame for your symptoms:

1. Thyroid issues

- Oxalate crystals have the ability to form in many different areas of the body, including the thyroid gland.

- The amount of thyroid hormone may be reduced if oxalate crystals are forming in the thyroid in women.

2. Kidney stones

- A very common form of oxalate toxicity is the presence of calcium oxalate stones, either in the kidney or other organs.

- Eighty to 90 percent of kidney stones may be due to high oxalate levels.9

3. Inflammation + tissue damage

- Typically, oxalic acid is expelled from the body via urination.

- However, if oxalic acid levels are high, oxalate crystals can form in bones, joints, blood vessels, the brain, and other organs, causing inflammation and tissue damage.10,11 They can also form in the kidneys and all the tissues in the body, including the skin, liver, and heart.

- There may be an association between oxalates and those with fibromyalgia who suffer from muscle aches and pains, as well as vulvodynia, which is pain in the reproductive tract due to inflammation and high oxalates in the vagina.12

4. Potentially higher than normal toxins

- Oxalates may also latch onto heavy metals like mercury and lead.

- This may trap them in the tissue and make it hard for the body to release these toxins.

5. Decreased immunity or anemia

- Oxalate crystals forming inside a bone could suppress functioning bone marrow cells, effectively leading to immunosuppression or anemia.13

- The oxalates get into the bone marrow and crowd out the cells that are producing the red and white blood cells.

- Therefore, the immune system may get impaired because the oxalates are crowding out the cells that are responsible for immunity.

6. Peripheral neuropathy

- For those who are genetically deficient in the enzyme AGXT, they may suffer from peripheral neuropathy.

- This is a condition that affects the peripheral nervous system, causing tingling, muscle weakness, and functional impairment.

Which foods contain high oxalates?

We’ll go into more detail about food in a moment, yet there are various healthy foods that many of us consume each day that are high in oxalates. These foods could be contributing to an overabundance of oxalates in the body (seen in the infographic below).

When high doses of vitamin C decompose, it can also form oxalates. If a person has excess iron or copper, this can accelerate the decomposition of vitamin C and speed up the oxalate process. If you have oxalates, and consume vitamin C, it’s said to stay below 500 mg daily for an adult, and 250 mg maximum for children.

Eighty to 90 percent of children with autism may have oxalate issues.8 Oxalate crystals can form in their eyes, which is common in children with autism since they’re on a diet that may not be giving them an adequate amount of calcium. Autistic children have benefited in numerous ways from adopting a low-oxalate diet.8

Almost all foods have small amounts of oxalates in them, so they’re truly unavoidable. Depending on the soil the food was grown in, and the more the food had to protect itself, the higher the oxalate level. And when high-oxalate foods are consumed continually, like spinach, this can lead to oxalates forming in the body.

However, there are many foods that are higher in oxalates than others, so for some people with varying symptoms, adopting a low-oxalate diet can have some major benefits. Scientific research has demonstrated that consuming certain oxalate-containing foods are likely to cause an increase in urinary oxalate.14 Thus, the consensus of many nephrologists, clinicians, and nutritionists is to limit oxalate intake to fewer than 40 mg per day.15

The foods and drinks listed below have been noted for their particularly high oxalate levels (often more than 7 mg per serving):

- Spinach, rhubarb, berries, sweet potatoes, leeks, beets, mature arugula, swiss chard, soy

- Gluten or any wheat-containing product

- Peanuts, almonds, and soybeans

- Tea, coffee, almond milk, chocolate, and cacao

- Condiments containing cinnamon, raw parsley, black pepper, ginger, or soy sauce

- Gelatin, certain meats*

*Some of the amino acids in certain types of meat can be converted by the body into oxalates and affect kidney stones.16

And, gelatin contains an amino acid called hydroxyproline that the body can convert into oxalates (for those living a Paleo lifestyle, please take note!). One study shows how a diet high in gelatin created high oxalate output in urine within a short period of time.17 If you’re eating these food items occasionally, it may not cause a problem. But, if you’re eating them daily, you may run into an issue.

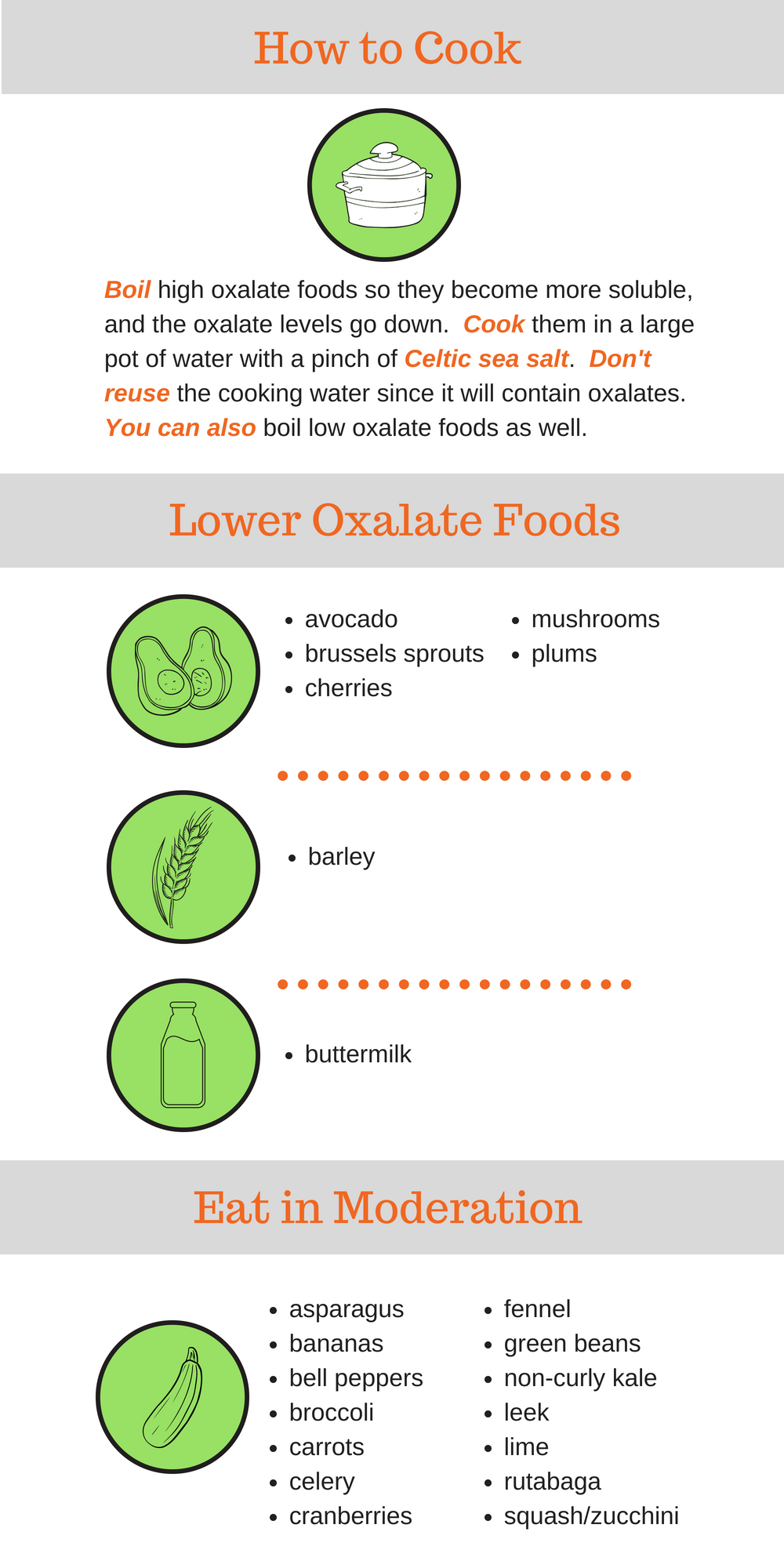

And if you decide to boil any of these foods, including high-oxalate foods, they become more soluble and the oxalate levels go down. So, be sure to boil your high-oxalate foods. After boiling high-oxalate foods in a large pot of water with a pinch of Celtic sea salt, remember to dump the cooking water since it contains the oxalates boiled out of the food.

Here are some foods that aren’t as high in oxalates and are recommended to eat instead:

- Avocado, brussels sprouts, cherries, mushrooms, plums

- Barley

- Buttermilk

These foods should be eaten in moderate amounts:

- Bananas, cranberries, green beans, rutabaga, asparagus, bell peppers, broccoli, carrots, celery, fennel, lime, non-curly kale, squash, zucchini, leek

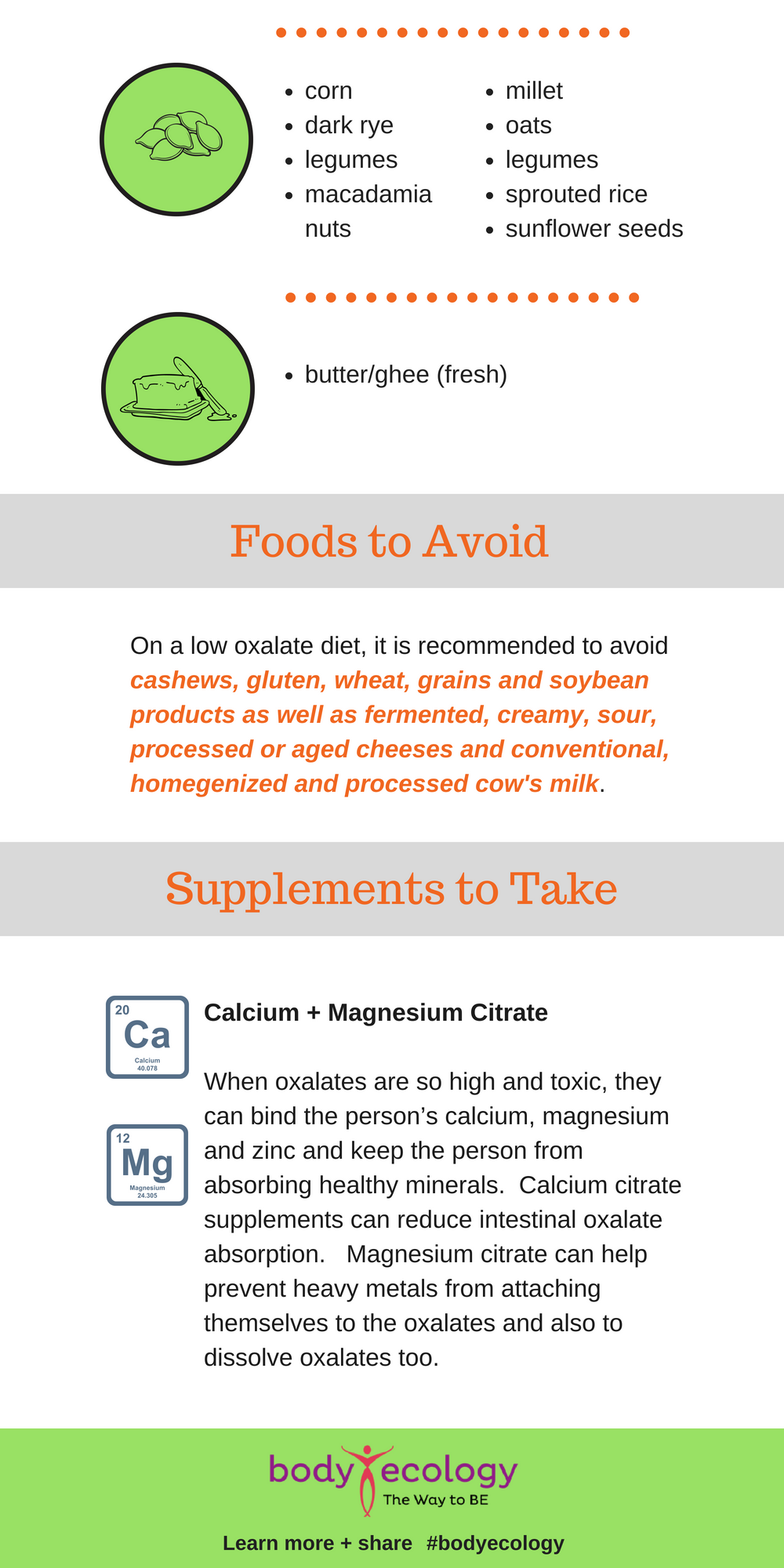

- Macadamia nuts, corn, millet, oats, sprouted rice, sunflower seeds, legumes, peas, dark rye

- Butter/ghee (fresh)

Please note: On a low oxalate diet, it’s recommended to avoid cashews, gluten, wheat, grains, and soybean products, as well as fermented, creamy, sour, processed, or aged cheeses and conventional, homogenized, and processed cow’s milk.

Here’s a tip too: Try downloading an oxalator app, like Oxalator or OxaBrow, to your phone or iPad. They may help take some confusion out of the decision process.

What can you do to help your symptoms?

There are tests that can identify if you’re indeed dealing with issues resulting from high oxalates (see below). The most effective step you can take, however, to help reduce oxalates is to remove the highest oxalate foods from your diet. Depending on the severity of the oxalate levels, it may take one week to a few months to get relief.

Let’s take a look at some suggestions:

1. Calcium + magnesium citrate

- When oxalates are so high and toxic, they can bind a person’s calcium, magnesium, and zinc and keep the person from absorbing healthy minerals.

- Calcium citrate supplements can help reduce intestinal oxalate absorption. And the magnesium citrate can help prevent heavy metals from attaching themselves to the oxalates, and also dissolve oxalates.

- You can use 300 mg of calcium citrate and 100 mg of magnesium citrate with each meal to prevent oxalates from being absorbed.

2. Low-fat diet

- The inability to fully digest fat or a diet high in saturated fat can also interfere with your ability to get rid of oxalates. Saturated fat binds to calcium, which usually helps oxalates exit the body.

- So, if high oxalates are present, it may be beneficial to stay on a low saturated fat diet. That way, the saturated fat doesn’t steal your calcium.

- Trying a supplement containing ox bile and the enzyme lipase may also help people who have a hard time digesting fats.

3. Lemon water

- By drinking water (small sips, not large gulps), your system can help flush the oxalates out.

- And if you add some lemon to the water, this may help prevent oxalates from sticking together.

- Staying hydrated is especially important for those prone to kidney stones.

4. N-acetyl glucosamine

- This may help to reduce pain caused by oxalates.

5. Vitamin B6

- Vitamin B6 is essential for energy production and can be depleted when dealing with an oxalate issue.

- It’s shown to help reduce oxalate production.18

- According to Weston A. Price, “The enzyme pyruvate kinase is involved in the last step in the body’s energy production and is strongly inhibited by oxalate. The same enzyme inhibition is largely responsible for Tourette syndrome. People with Tourette syndrome, however, have strep antibodies that inhibit this enzyme. Oxalates also strongly inhibit the same enzyme. This enzyme works much better in the presence of high amounts of vitamin B6.”

6. Chondroitin sulfate

- This may help to prevent calcium oxalate crystal formation.

7. Omega-3 fatty acids

- Present in fish and cod oils, these fatty acids may help reduce and prevent oxalate-related issues.

As nutritional genomics experts, we help address oxalate reduction and prevention with helpful bacteria and fermented foods. A few recommendations are:

- Our InnergyBiotic drink containing lactobacillus, acidophilus, and bifidobacterium, which may help degrade oxalates.

- Our Veggie Culture Starter containing many friendly microorganisms that may help control oxalates.

How to get tested for an oxalate issue

The Great Plains Laboratory offers a comprehensive Organic Acids Test (OAT) to screen through urine for oxalic acid; arabinose (candida albicans indicator); and pyridoxic acid (vitamin B6 indicator), among many other markers like bacteria, fungus, yeast, folate, and those associated with genetic forms of oxalate problems.

To test for genetic deficiencies, you can try Self Decode genetic testing. It’s highly recommended that test results be discussed with your doctor and a versed nutritionist who can help you transition to a low-oxalate lifestyle.

It’s also important to mention that patients who have healed from an oxalate issue noted that lowering their oxalate intake slowly was beneficial. When too many oxalates leave the body at once, it can cause “oxalate dumping,” which can create additional unpleasant symptoms. The same holds true for re-introducing them to your diet. Coupled with the appropriate protocol, it’s smart to start out with low oxalate foods, then move up from there slowly.

REFERENCES:

- 1. Shaw, W.“Oxalates: test implications for yeast and heavy metals”. Great Plains Laboratory. http://www.greatplainslaboratory.com/home/eng/oxalates.asp. Visited 12 September 2015.

- 2. Takeuchi, H., Konishi, T., and Tomoyoshi T. “Detection by light microscopy of Candida in thin sections of bladder stone” Urology, vol. 34 (6), 1989. pp. 385-387.

- 3. Takeuchi, H., Konishi, T., and Tomoyoshi T. “Observation on fungi within urinary stones.” Hinyokika Kiyo, vol. 33 (5), 1987. pp. 658-661.

- 4. Shaw, W. “Oxalates: test implications for yeast and heavy metals”. Great Plains Laboratory. http://www.greatplainslaboratory.com/home/eng/oxalates.asp. Visited 12 September 2015.

- 5. Xingsheng Li, Melissa L. Ellis, and John Knight. “Oxalobacter formigenes Colonization and Oxalate Dynamics in a Mouse Model.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4495196/. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015 Aug; 81(15): 5048–5054. Published online 2015 Jul 7.

- 6. Sahin, G., Acikalin, M., and Yalcin, A. “Erythropoietin resistance as a result of oxalosis in bone marrow.” Clinical Nephrology vol. 63 (5), 2005. p. 402.

- 7. Shaw, W. “Oxalates: test implications for yeast and heavy metals.” Great Plains Laboratory. http://www.greatplainslaboratory.com/home/eng/oxalates.asp. Visited 12 September 2015.

- 8. Shaw, W. “Oxalates Control is a Major New Factor in Autism Therapy.” Great Plains Laboratory. http://www.greatplainslaboratory.com/home/eng/oxalates.asp. Accessed on November 27, 2015.

- 9. Huang Y, Zhang YH, Chi ZP, Huang R, Huang H, Liu G, Zhang Y, Yang H, Lin J, Yang T, Cao SZ. The Handling of Oxalate in the Body and the Origin of Oxalate in Calcium Oxalate Stones. Urol Int. 2020;104(3-4):167-176. doi: 10.1159/000504417. Epub 2019 Dec 5. PMID: 31805567.

- 10. Ghio, A., Roggli, V., Kennedy, T., and Piantadosi, C. “Calcium oxalate and iron accumulation in sarcoidosis.” Sarcoidosis Vascular Diffuse Lung Disorder vol. 17 (2), 2000. pp. 140-50.

- 11. Hall, B., Walsh, J., Horvath, J., and Lytton, D. “Peripheral neuropathy complicating primary hyperoxaluria” Journal of Neurological Science vol. 29 (2-4), pp. 343-9.

- 12. Shaw, W. “Oxalates Control is a Major New Factor in Autism Therapy.” Great Plains Laboratory. http://www.greatplainslaboratory.com/home/eng/oxalates.asp. Accessed on November 27, 2015.

- 13. Sahin, G., Acikalin, M., and Yalcin, A. “Erythropoietin resistance as a result of oxalosis in bone marrow.” Clinical Nephrology vol. 63 (5), 2005. pp. 402-4.

- 14. The Children’s Medical Center of Dayton (OH). “Diet and Oxalate.” pub. 14 July 2015. http://www.childrensdayton.org/cms/resource_library/nephrology_files/5f5dec8807c77c52/lithiasis__oxalate_and_diet.pdf.Visited 11 September 2015.

- 15. University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. “Low Oxalate Diet.” http://www.pkdiet.com/pdf/LowOxalateDiet.pdf. Visited 10 September 2015.

- 16. Turney BW, Appleby PN, Reynard JM, Noble JG, Key TJ, Allen NE.(2014) “Diet and risk of kidney stones in the Oxford cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC).” European Journal of Epidemiology. 29(5):363-9.

- 17. J Knight, J Jiang, DG Assimos, and RP Holmes. Hydroxyproline ingestion and urinary oxalate and glycolate excretion. Kidney Int. 2006 Dec; 70 (11): 1929–1934.

- 18. Sangaletti O, Petrillo M, Bianchi Porro G. Urinary oxalate recovery after oral oxalic load: an alternative method to the quantitative determination of stool fat for the diagnosis of lipid malabsorption. J Int Med Res. 1989 Nov-Dec;17 (6):526-31.